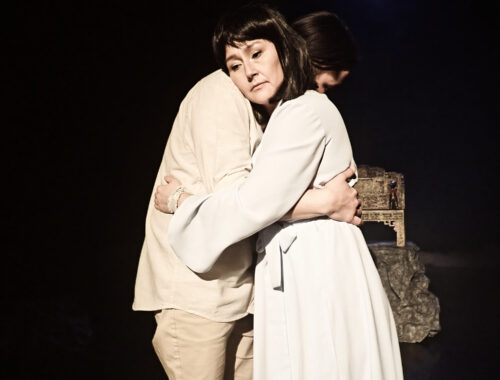

‘The Little Goddess’: A tale of beliefs, change, and choice

How do the human belief mechanisms change through time, and how can the change affect individuals, who are rooted in those beliefs? Those are just some of the questions that the theatrical performance, ‘The Little Goddess’, tries to unravel through a mixture of the Western and Eastern forms of theater production.

The story of a living goddess

‘The Little Goddess’ is a performance told by the narrator, Haru. He speaks about the memories of his lost lover, the former living goddess embodied by Tara. The play is structured in three layers of past, present, and future, that intertwines through the eyes of the narrator. ‘The Little Goddess’ revolves around themes that showcases the conflict between old tradition/belief and new ideas, as well as questioning humans’ belief mechanisms. The performance is told in the mixed styles of magical realism and realism, showing the life cycle of one girl, who is chosen to be a living goddess in the country, at the dawn of political uprising and cultural shift.

The play was first created in 2018, in the Estonian National Drama Theater. It is inspired by the living goddess practice in Nepal, and the historical Shinto ritual in Japan. In the Greenlandic production, the play has also incorporated some essence of traditional beliefs of Greenland.

The woman behind the play

Izumi Ashizawa is the director and writer behind the performance. She has, for the past 20 years, produced and directed a number of plays around the world, and has given audiences once-in-a-lifetime performances showcased through mixtures of western and eastern theatrical forms.– Throughout these many years, I’ve learned that, in every culture, performances were rituals for spirits or gods. A form of offering. And I connect those types of performances to child’s play, and I’ve always had an interest in performances ever since I was a child, says Izumi Ashizawa and continues. – When I was young, I used to perform for the spirits. I would make posters, put them on my tricycle, and start to advertise for my show, inviting the spirits throughout my house to come and watch. Then I would perform. Alone. But I thought I was being watched by the spirits. So, that was the beginning of my theater, she ends while laughing.

A theatrical twist

The play is made of both the Western (which focuses on speech) and the Eastern (which focuses on senses) theater forms. Therein lies the structure of having a narrator, whilst also performing with puppets, masks, and movement. That is also how ‘The Little Goddess’ is shown. In the beginning of 2000, Izumi Ashizawa started to mix traditional Japanese theatrical forms with different mythologies, such as Greek mythology. But she made a twist.– Usually, Greek has heroes portrayed by men. I, however, always create spirits or women as the protagonists. Depicting common mythology from the victim’s point of view, using Japanese concepts of mask-play, movement, and aesthetics. It then started to develop from there, and now, my plays have become more based on cultural contexts, instead of mythology.She hasn’t just mixed theatrical ideas. With this play, she has also created a twist of interactive performance – and alternative endings.

Throwing away the script

Izumi Ashizawa has always made sure to create plays, that cater to the audience of the country that the performances are shown in. So, when ‘The Little Goddess’ was shown in Estonia, the cultural contexts of the play reflected the Estonian culture. In Greenland, the cultural contexts then catered to the Greenlandic audiences instead. The overall themes that ‘The Little Goddess’ touches upon are being different, confronting traditions, life, death, and love. The play also goes through the questions of child abuse and suicide among the youth in a mythological timeframe and through a poetic form. Because of the heavy themes of the play, Izumi Ashizawa came up with something different.– I was aware of the social issue in Greenland before I got here. Specifically with youth suicide. So, when I was invited to do this performance, we, the national theater and I, decided that we wanted people to be able to talk about the issues through the performance. To have the young open up and speak. I really had to think. How can we draw the youth in and give them a form of empowerment? That’s when we had the idea of, not just having the audience see the performance, but also be able to be a part of it, she says contemplatively.The Little Goddess was supposed to have been in theaters around autumn of 2020. But because of the pandemic, the plans changed. And maybe it was for the better.

– In the beginning, we created a plan, where the audiences could have open sessions with the on-location psychologist that we had prepared. And up until January 2022, that was the plan. I was actually in transit in Iceland when the new idea struck me. Alternate endings. Just like a game that can have alternate endings depending on one moment, I wanted the performance to have the same structure. So, I gave the audiences a chance, a choice. If you could change one thing about the performance to change the consequence of the story. What would you change? Through this method, I wanted my play to become a steppingstone, because, then maybe, they could change their lives too.By giving the audiences a choice to change the consequence of the story, Izumi Ashizawa has done something, that no other director or writer of plays have done before. She threw away the script, deconstructed what had been made, and gave the audience a chance to be heard. The selected new scene is then completely improvised by the actors on the spot, while the on-location psychologist talks with the audience about what they would change – and why.

– The audiences so far, have loved the twist at the end. I have noticed a surprising similarity in what the audiences want to have changed. This is in both children and adults. The mother’s rejection scene of Tara. So, I believe that this is the scene, that is probably hard for certain audiences, and is probably a trigger for most people. Or that they at the very least can connect it with their own experiences in one way or another.

Bringing the play to Greenland

When met with the questions, ‘why Greenland?’, and ‘why this play?’, Izumi Ashizawa had a clear answer. It is because of the similarities between the traditional beliefs of Greenland and her home country, Japan.– There are many creatures appearing in the play, and they are, in a way, spirits as well. And it’s deeply related to the animistic beliefs or ideas, that all the living creatures and objects around you, possess spirits. So, because Tara is a child in a specific situation, and she starts to develop the idea that she can open up the mystical, or in this case, the imaginary world, which in principle is a child’s game, but also a very animistic belief that our Japanese culture has, as well as Greenland. And as this is something that we have in common in both of our cultures, I thought that the Greenlandic audience may really appreciate or find the similarities through the creatures. We are talking about undertones of difficult subjects in the layers of the imaginary world, where the spiritual creatures that the Greenlandic audience are really accustomed to gets shown.

The tour

After the performances in Nuuk, Greenland, the play is brought to the rest of the country. During the tour, six separate cities get visited. Among the cities are: Ilulissat, Qeqertarsuaq, Aasiaat, Sisimiut, Maniitsoq, and Qaqortoq.

The tour started on the 21st of March 2022 and will end on the 13th of April 2022.

Last remarks from the director and writer

– Without the different grants, we wouldn’t have been able to tour, nor would I have been able to actually arrive to Greenland and stay during the rehearsals for the past two months. We also changed some of the costumes for the play. We did that, so we could match the colors of the robes to the Greenlandic nature. And that definitely wouldn’t have been possible without the support.

“Thank you for changing my life. Your choice changed my past. You changed my life, so now you can change yours too. Now, what do YOU do? – Male writer, Haru from ‘The Little Goddess’.

Facts about the play:

Director, writer, and musical composition arranger: Izumi Ashizawa

Translator: Hans-Henrik Suersaq Poulsen

Scenography, costumes, and props: Kristjan Suits

Assistant to Kristjan Suits: Camilla Nielsen

Actors: Hans-Henrik Poulsen, Kimmernaq Kjeldsen, Ane-Marie Ottosen, Ujarneq Fleischer, Klaus Geisler, Nukakkuluk Kreutzmann, and Miki Petrussen

Lights, posters, and program design: Gerth Lyberth

Moderator: Inuk L. Borup Bang

Production: Nunatta Isiginnaartitsisarfia (The National Theater of Greenland)

Productions leader: Pilutaq Lund

Sponsors: NAPA – Nordens Institut i Grønland, Selvstyrets Kulturmidler, Selvstyrets Tips- og Lottomidler, Sermeq Puljen, Aningaasaateqarfik Juullip Nipitittagaa (Julemærkefonden), Dronning Margrethes og Prins Henriks Fond, Helene og Svend Junges Fond, Air Greenland.

- Children and youths, Culture, Greenland, Identity, News, Supported projects

- Foto af Izumi Ashizawa

Other news

NAPA has received the first application in their new application system

NAPA has just launched a new website and new application module for their Cultural Support Program. Shortly afterwards, the first application for support landed: A project concerning a creative workshop for children and young people in Ilulissat and Maniitsoq. With the new application system, it

Nordic Arctic Cooperation Programme funds distributed: Sustainable projects in Greenland receive support

The Nordic Council of Ministers’ pool for the Nordic Arctic Cooperation Programme, which aims to promote Nordic international cooperation in – and for the benefit of – the Arctic, has allocated funds for a number of exciting projects, including Siu-Tsiu and MIO. The Nordic Council

Prize competition about Energy in the Arctic

Nordic Energy Research (NER) aims to support Nordic energy co-operation. In connection with this, they hold a Nordic Energy Challenge every year, where players in energy sectors can submit their ideas for this year’s competition theme. This year, the theme is Energy in the Arctic.

NAPA will be participating in a webinar on Nordic language communities

Based on NAPA’s podcast (N)ORD on Nordic languages and words NAPA has been invited to participate in the Nordic Council of Ministers’ webinar “Does the Nordic Region have a language community?” The webinar takes place on Thursday 18 March at 13-14.30 (CET). Malin Corlin will